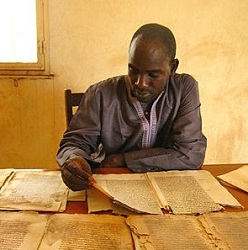

I first met Abdel Kader Haidara eight years ago, when I flew to Timbuktu to write about the country's rediscovery of its literary heritage. Adds Diakité: "He feels as much responsibility for them as he does for his own family." She worked side by side with Haidara in Bamako to raise $1 million from benefactors in Europe, the U.S., and the Middle East to finance the rescue effort. "Abdel Kader feels as close to the manuscripts as he does to his children," says Stephanie Diakité, an American attorney who became entranced by the works 20 years ago during a visit to Mali and decided to make their preservation her life's calling. I had lots of friends, lots of partners, people who gave me a lot of advice, so that I never felt completely abandoned." A Grand Culture Rediscoveredįor Haidara, 50, the scion of a distinguished family of scholars and collectors from Timbuktu and other towns along the Niger in northern Mali, the rescue marked the culmination of a long career as a champion of the country's cultural patrimony. So we just had to keep working, doing what we could do. "I could never have imagined such a thing happening just a few months before. All we could do was work," Haidara told me in Bamako, of that difficult time. "We were completely traumatized by the jihadists. In the last phase of the rescue, during the French military intervention of January 2013 that drove AQIM from northern Mali, a French helicopter nearly fired missiles at a boat bringing manuscripts downriver-the pilots suspected that Haidara's assistants were smuggling guns.

#Ancient timbuktu manuscripts full

Malian government soldiers often broke open trunks full of manuscripts in a search for weapons, roughly pawing through the fragile volumes. Bandits captured a boat full of books on the Niger River and held it for ransom. AQIM operatives stopped, searched, and arrested Haidara's couriers. "Traumatized by the Jihadists"īut the face-offs with the jihadists kept coming. After 24 hours in custody, the Islamic police let him go. Having fled Timbuktu to live in self-imposed exile in Bamako, Haidara manned the phones, calling imams, neighborhood leaders, and other librarians, who came forward with documents and affidavits attesting to Touré's role as curator.

"They said, 'The proof is there you were robbing this library.' I said, 'It belonged to me, and I was moving it to a more secure location.'" He bought himself time, but his fate was unclear. Thinking fast, Touré, who is well grounded in Islamic studies, cited hadiths and Koranic verses stating that incontrovertible proof of a misdeed was required before punishment was meted out. "They had already started chopping off hands in public places." "I risked losing my hand, my foot," Touré said. He was charged with theft, a serious crime under sharia. Islamic police arrested the curator and and dragged him to the commissariat of the Islamic police. "He said, 'You're stealing them,'" Touré recalled one recent afternoon in the Malian capital of Bamako. Hamaha shone a flashlight in Touré's face and demanded that he open the chest. One night when he was leaving work with a trunk full of manuscripts destined for hiding, Touré came face-to-face with Oumar Ould Hamaha, one of AQIM's most inflexible zealots.

.jpg)

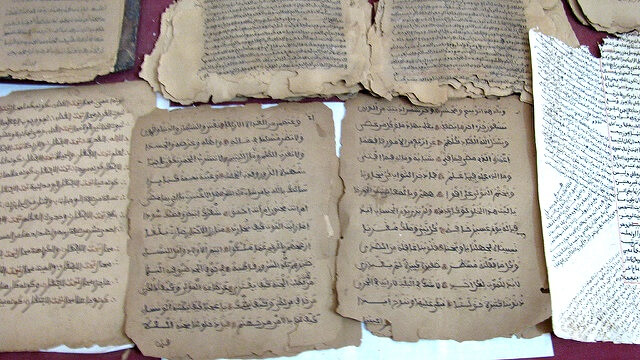

There were many close calls, including one involving Haidara's nephew, Mohammed Touré, a 25-year-old curator at the library. Over nine traumatic months, Haidara and his team rescued 350,000 manuscripts from 45 different libraries in and around Timbuktu and hid them in Bamako, more than 400 miles from the AQIM-controlled north. Kant and Hegel and Hume did not know anything about this."

So the presence of these books had high, high stakes, going back to the 18th century. "The absence of writing, of books, was seen as a reflection of the subhuman position of the Africans. "And unless you have those, you are not a civilization, which was a pernicious argument that provided justification for the slave trade," Gates said in a recent interview. Harvard scholar Henry Louis Gates, Jr., who visited Timbuktu and Haidara in 1996, explains that Hegel, Kant, and other Enlightenment philosophers contended that Africa had no tradition of writing, and therefore no history and no memory. The extremists' inroads, militarily and culturally, held a sad irony: Haidara as a scholar and community leader had made it his life's work to document, as never before, Mali's achievements as an ancient center of progressive thought, including Islamic teachings that were anathema to the fanaticism that AQIM was now attempting to spread through the West African country.Īnd Haidara's manuscripts were precious for what they said more broadly about Africa's history.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)